Ten-year-old Will Bartold plays roller and street hockey. When he started complaining about his arm hurting and a lump formed in the area of his left proximal humerus, his parents thought it was because of the rough-and-tumble nature of the game he loves. But then the lump began to grow and the pain increased.

Ten-year-old Will Bartold plays roller and street hockey. When he started complaining about his arm hurting and a lump formed in the area of his left proximal humerus, his parents thought it was because of the rough-and-tumble nature of the game he loves. But then the lump began to grow and the pain increased.

“As soon as our pediatrician, Dr. Alla Dorfman, felt Will’s arm, she said she wanted an image taken immediately,” says Will’s mom, Sheri Bartold. “We went to a local diagnostic imaging center, where they usually tell you the results right away. This time, the technician called me back and told me Dr. Dorfman was on the phone for me. The first thing she said was, ‘I love you my darling,’ and I knew this was something serious. She told me there was a mass, and we needed to see an orthopaedic surgeon at Children’s Hospital.”

That’s where Washington University physician Terra Blatnik, MD, pediatric orthopaedic surgeon at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, confirmed the diagnosis for the Bartolds: Will had osteosarcoma. The Bartolds were referred to Regis O’Keefe, MD, PhD, the Fred C. Reynolds Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery and chair of the department of orthopaedic surgery at Washington University School of Medicine. Dr. O’Keefe is an expert in treating osteosarcomas in both children and adults, a level of knowledge needed to treat Will’s complex case.

THE GOOD NEWS AND THE BAD

“St. Louis Children’s Hospital is particularly suited for treating children with cancers of the bone— osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma—because of the expertise that exists beyond orthopaedic surgery,” says Dr. O’Keefe. “For example, Will’s treatment called upon the skills of vascular surgery and pediatric oncology in order to achieve the goal we have for all of these patients; namely, preserving their limbs and function, and thus setting them on a path for productive lives after experiencing a potentially debilitating disease early in their lives.”

Osteosarcoma’s stealthy nature means tumor cells not only attack bone but also metastasize mainly to the lungs, where they are initially hard to detect. For that reason, the established protocol is to begin treatment with 8-12 weeks of chemotherapy prior to surgically removing the primary tumor. David Wilson, MD, PhD, Washington University pediatric oncologist at Siteman Kids at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, oversaw Will’s chemotherapy treatment.

“The chemotherapy is helpful in killing the primary tumor cells, but it is most useful in killing the cells that have metastasized to the lungs,” explains Dr. O’Keefe. “Prior to the development of chemotherapy, the treatment for these children was amputation at the site of the bone cancer. Despite removing that primary tumor, however, 90 percent of patients died because of the micrometastases that had already traveled to the lungs.”

Today, how well an individual patient’s primary tumor reacts to the chemotherapy indicates how well cancer cells in the lung are being killed. For instance, if 40 percent of cells are destroyed at the local site, 40 percent are being killed in the lungs.

The good news for Will was that the chemotherapy killed 100 percent of the tumor cells at his primary site, and that meant an excellent prognosis for his recovery.

The bad news was that his tumor was spreading toward the growth plate in his shoulder.

A DELICATE, COMPLEX SURGERY

“In addition to being extremely close to the growth plate, the tumor was near key nerves and structures that would determine how much use Will would have of his arm,” says Dr. O’Keefe.

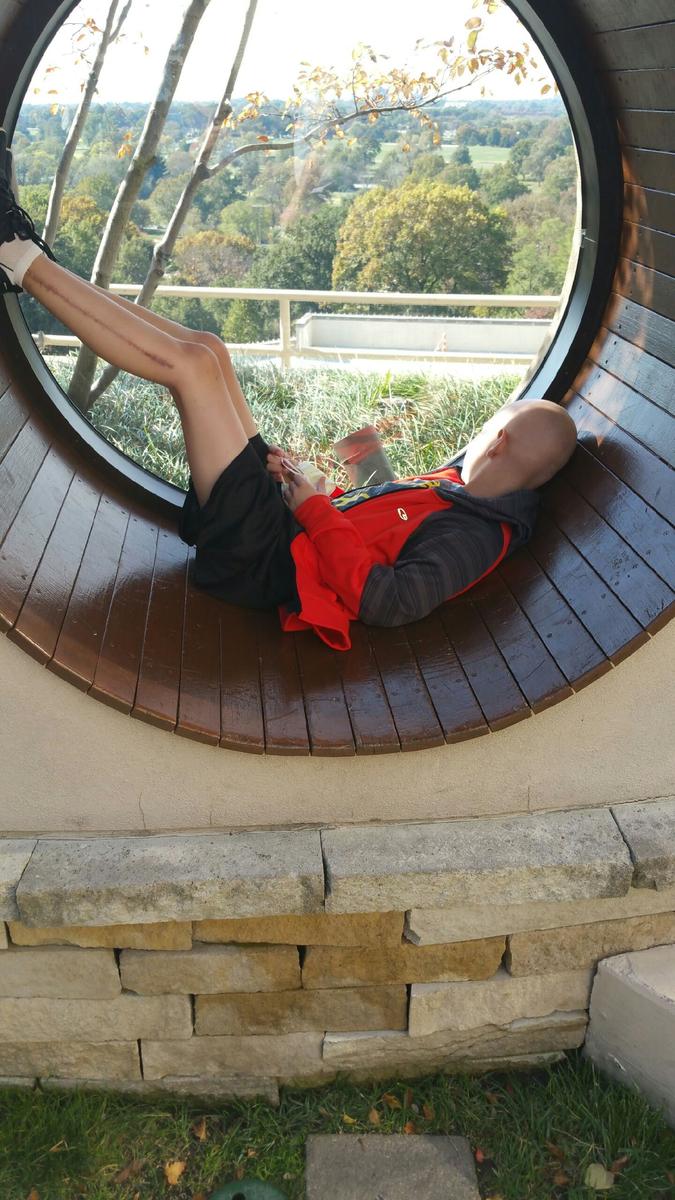

The surgery involved precise, delicate cuts in an area with just millimeters between the tumor and growth plate. A 12-15 centimeter section of bone in Will’s proximal humerus was removed, which meant that the small part of the remaining proximal humerus, the growth plate and shoulder joint were separated from the distal part of the arm bone by a large gap.

“The solution to this surgical problem is another illustration of why these complex cases can only be performed at facilities like St. Louis Children’s Hospital,” says Dr. O’Keefe. “Microvascular surgeons Martin Boyer and Daniel Osei removed Will’s left fibula along with its blood supply and placed the bone in the gap that existed in Will’s arm. They then connected the microscopic blood vessels from the fibula to those of the proximal humerus and distal arm bone.”

The critical nature of the surgery is illustrated by what could have been the reality for Will. “If we hadn’t been able to save the growth plate, we would have had to also remove the entire proximal humerus. Will’s arm would have stopped growing, and he wouldn’t have a shoulder joint,” says Dr. O’Keefe. “The result could have been a short extremity that he may have been able to move five to 10 degrees forward and laterally.”

Dr. O’Keefe notes that although removing Will’s fibula meant an additional surgery—“borrowing from one place to meet the desperate need in another”—the surgeons knew the functional problems Will may experience in his leg likely would be minimal. And according to Sheri Bartold, that has been the case.

“At first when they suggested using the fibula, our concern sort of shifted from Will’s arm to his leg. Would he be able to run, would it be another thing for him to overcome?” says Sheri. “Will had to wear a brace on his leg for a little while, but at this point, if you didn’t see the scar on his leg, you wouldn’t notice anything different about his walk or how he runs.”

CONTINUING CHEMOTHERAPY

Less than a month following his surgery, Will again began undergoing chemotherapy treatments to ensure destruction of any lingering tumor cells. Once Will’s eight cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy are completed, he will be approaching the one-year anniversary of his initial diagnosis.

“Because patients with bone cancers are in treatment for a long time, the whole care team needs to take a family-centered approach that provides education and support to the patients and their families,” says Dr. O’Keefe.

Will also benefited from the loving support of his parents, Sheri and Mike, and older sister Morgan. “Will does gets overwhelmed sometimes, and he takes medication for that. His appetite is not what it should be, and he has trouble sleeping. But his attitude is that this isn’t going to get him down,” says Sheri. “And for us, we developed such faith in everyone involved in Will’s care. We literally put our son’s future in their hands, and we are so grateful for their skill and compassion.”

A PROMISING FUTURE

Only 10 percent of osteosarcomas recur at the primary tumor site, and at this point in his treatment, there is no evidence of metastasized tumor cells in Will’s

lungs. Once he completes chemotherapy, Drs. O’Keefe and Wilson will follow Will for years to come.

“All indications point to Will resuming his active participation in sports and other aspects of his life,” says Dr. O’Keefe. “And that is what is so rewarding as we continue to follow these patients to maturity and see them enjoying a fulfilling life.”

To speak with Dr. O’Keefe or to make an appointment, call Children’s Direct at 800.678.HELP (4357).