Special Consideration

Indications for Neurosurgical Repair of Brachial Plexus

Preoperative Evaluations

Potential Complications

Surgical Procedures

Timing for Functional Improvement

Outcome

Special Considerations

- Surgical repair of the brachial plexus restores incomplete arm and hand strength.

- Optimal timing for surgery varies with individual patients.

- Reconstruction of the brachial plexus is performed in various fashions.

- No neurophysiology test in infants can reliably identify which portion of the injured brachial plexus requires resection and repair with nerve graft.

It is important to remember that in the great majority of patients, although surgical repair will result in improved function of the arm, it will not restore complete muscle strength. Because of this, and the fact that many patients will improve to varying degrees without surgery, great care is needed when selecting patients for surgical treatment.

Optimal timing for surgical intervention depends on the severity of the brachial plexus injury. For example, infants with suspected nerve root avulsion or ruptured brachial plexus require early surgical exploration. On the other hand, infants with less extensive injury will show clinical improvement during the first 3-6 months and thus require more time before a decision can be made regarding the need for surgery.

In a given patient, direct surgical repair of the brachial plexus depends on the location and extent of the nerve injury. Reconstruction using nerve grafts is carried out in a number of ways, and the surgeon should make decisions based on his/her experience.

A unique problem in brachial plexus surgery in infants is that no neurophysiology test allows reliable identification of the portion of the brachial plexus that requires resection and repair with nerve grafting. We base our decision on the result of direct electrical stimulation of the brachial plexus, the severity of neuromas seen at the time of exploration, and infant's muscle weakness prior to surgery.

Indications for Neurosurgical Repair of Brachial Plexus

- Flaccid entire upper extremity at 2 months

- Less than antigravity muscle strength with Horner’s syndrome or Pseudomeningocele at 3-4 months

- Less than antigravity strength of any muscle at 4-6 months

The complete absence of improvement results from a severe injury, including nerve root avulsion or rupture of the brachial plexus. These infants would require early brachial plexus repair surgery.

Horner’s syndrome includes droopy eye and small pupil; the presence of this sign indicates injury to the lower brachial plexus (C8-T1) close to the spinal cord; it can be associated with avulsion of the nerve roots. Pseudomeningocele is a finding on MRI scan which suggests possible avulsion of the particular nerve root.

If infant shows some contraction in muscles at the age of 2-3 months, we recommend continuous physical therapy until 4-6 months.

Preoperative Evaluations

- Muscle strength assessment

- Chest x-ray or ultrasound

- Cervical spine MRI

- Videotape

Muscle strength in the arm and hand is measured and documented by physicians and therapists. Changes in muscle strength are noted after surgery and in follow-up examinations.

Chest x-ray is taken primarily to check for diaphragm paralysis due to phrenic nerve injury.

Cervical spine MRI is obtained to determine the presence of pseudomeningocele (pocket of cerebrospinal fluid) along the spinal nerve root, which may indicate detachment of the nerve root from the spinal cord.

Videotape is used prior to surgery, at 6 months after surgery, and at subsequent follow-up visits to document the clinical course of each patient.

Potential Complications

- Phrenic nerve injury

- Injury to the lung and major blood vessels

- Wound infection

- Additional injury to brachial plexus

Injury to the phrenic nerve, which is adjacent to the upper trunk of the brachial plexus, can cause diaphragm paralysis. Reconnecting the nerve allows the paralysis to eventually resolve.

Injury to the lung will cause pneumothorax. Injury to the subclavian artery and vein is also possible.

Additional injury to the brachial plexus is possible but can be easily avoided. It should be noted, however, that a decrease in muscle strength can follow reconstruction of the brachial plexus with nerve grafts. This occurs because a functioning nerve root is sometimes cut and connected to the other part of the brachial plexus using nerve grafts. The muscle strength will most likely return with time, and the risk of such complications is very small.

Wound infection can occur around the incisions in the neck.

Surgical Procedures

Three basic operative procedures are performed:

- Brachial Plexus repair with grafts

- Nerve Transfer Procedure

1. Brachial Plexus repair with grafts

A skin incision is made along the neck and sometimes extended to the shoulder. When a nerve graft procedure is needed, donor nerve is used.

For upper brachial plexus injury (Erb's palsy), the brachial plexus above the clavicle is exposed. For total brachial plexus injury, the entire brachial plexus may be exposed above and below the clavicle. Neuromas are almost invariably present, and additional pathology such as scar tissue surrounding the brachial plexus, avulsed nerve root, and ruptured trunk of the brachial plexus may also be present.

Once the abnormal brachial plexus has been exposed, muscle contractions in response to direct electrical stimulation of the nerve root and the other part of the brachial plexus are examined. Nerve action potential study is impossible in infants because of the small operative field and has not been validated for brachial plexus surgery in infants.

In any event, no or minimal muscle contraction during electrical stimulation to a given nerve root is a strong indication for nerve grafting procedure. On the other hand, good muscle contraction during electrical stimulation can be produced by only a small number of intact axons, which are insufficient for functional recovery without nerve grafts.

Thus, we take into account the extent of a neuroma and an infant's preoperative muscle strength when making decisions about the need for nerve grafts. In general, we prefer resection of the neuroma combined with nerve grafting, especially for upper and middle trunk injuries. But nerve graft for the lower trunk injury is done only when the infant has no muscle contraction in the wrist and hand preoperatively or has avulsed nerve roots. Otherwise, we tend to do neurolysis of the lower trunk. This conservative approach is based on the fact that the functional outcome of nerve grafting of the lower trunk is not as good as on the upper and middle trunk.

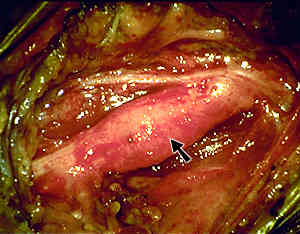

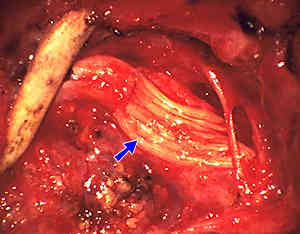

The spinal nerve root, trunk (black arrow), and other parts of the brachial plexus most often are surrounded by nonneural scar tissue (blue arrow). This is removed to free up the brachial plexus. When the neuroma is not extensive, the infant has some muscle strength, and electrical stimulation elicits strong muscle contraction, neurolysis alone is performed. Also, neurolysis is a part of the nerve grafting procedure. In other words, neurolysis needs to be done before nerve grafts are placed.

Reconstruction of the brachial plexus with nerve graft can produce gratifying results, particularly in infants with upper trunk injury. This operative photograph illustrates a form of nerve grafts used for brachial plexus surgery. A number of variations of nerve grafting procedures are utilized, depending on the location and extent of brachial plexus injury. It is important to note that nerve grafting offers the best chance for infants whose injury is extensive and for whom the probability of spontaneous recovery is minimal.

2. Nerve Transfer Procedure

Nerve Transfer Procedures are sometimes performed if the deltoid and/or biceps are weak alone. It is also performed if the brachial plexus repair with grafts fails to provide optimal improvements. Nerve transfer can be performed up to the age of 24 months.

An incision is made in the underarm region and extended possibly along the inside of the upper arm to expose the appropriate nerves. The nerves are stimulated with an electrical current and muscle responses are tested. A small portion of a donor nerve is then transferred to a recipient nerve to promote nerve input to the desired muscle group. The surgery takes about 2 hours.

Potential Complications

- Wound infection

- Failure to benefit from surgery

- Weakness of muscles supplied by the donor nerve

Timing for Functional Improvement

Improvement in deltoid and biceps muscle strength is detectable around 6 months after surgery, although some infants show improvements sooner. Muscle strength will increase gradually over the next 18 months. Improvement of the forearm and hand muscles is detectable around 8 months and continues for 3-4 years.

Overall Outcome Rate

- Improvements start typically 4-6 months following surgery

- Patients may show improvements up to the age of 5 years.

- If no improvements 1 year from the date of surgery, the child is unlikely to improve

Our own study described outcomes in the first series of patients who underwent brachial plexus surgery at the St. Louis Children's Hospital.

- Age at time of surgery 3-35 months

- Injuries most commonly involved C5 and C6 (59% of all injuries)

- If C7 root is included, 74% injury sites were localized to the upper brachial plexus. Likewise, nerve root avulsion most commonly involved the C5-7 nerve roots.

- Neurolysis, neurotization, nerve grafting, or a combination of those procedures were performed on the patients.

- Patients were followed from 7 to 45 months.

- Seventy-five percent of those who underwent one of the surgical procedures and were followed after surgery gained antigravity strength in the biceps and triceps muscles. In this group of patients, the biceps and triceps had favorable outcomes compared to the deltoid.

- Neurolysis and nerve grafting appeared superior to neurotization.