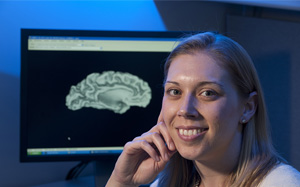

In search of the best way to protect the brain development of children with congenital heart disease

Neonatologist Cynthia Ortinau, MD, has seen the pain expectant parents go through in learning their baby has a serious heart defect. It’s a difficult conversation that gets even harder when telling parents about the link between congenital heart defects and developmental delays.

Neonatologist Cynthia Ortinau, MD, has seen the pain expectant parents go through in learning their baby has a serious heart defect. It’s a difficult conversation that gets even harder when telling parents about the link between congenital heart defects and developmental delays.

“Right now, we can tell parents what to expect in terms of the surgical and medical interventions available for their newborn’s heart condition. Unfortunately, we can’t do the same for their long-term development,” says Dr. Ortinau, Washington University neonatologist at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. “That uncertainty is what drives us to learn more about how and why brain development is different in these babies.”

In 2013, Dr. Ortinau began research to find these answers after receiving a grant from the Children’s Discovery Institute (CDI), a research partnership between St. Louis Children’s Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine. Dr. Ortinau’s hope is to one day be able to say: “yes, your baby has a heart defect that we’ll begin treating, and he’s what we are going to do to protect your baby’s brain development along the way.”

For her CDI pilot study, Dr. Ortinau’s research team recruited 39 patients who had an MRI of the baby’s brain before birth. Follow-up imaging and development testing took place after the children were born. This study was groundbreaking because it showed the feasibility of using MRI technology on babies before they are born.

“The study required us to come up with special protocols to capture pictures of the brain while the baby was moving around inside of the mother,”Dr. Ortinau says. “We were one of a select few centers around the country doing this type of work to advance fetal brain imaging, especially in babies with congenital heart disease.”

Shortly after launching this project, Dr. Ortinau decided to move her work to Brigham and Women’s Hospital to continue her mentoring relationship with Terrie Inder, MD, a pioneer in the use of MRI scans of premature infants to predict future delays in development. In Boston, Dr. Ortinau worked with a large team studying cardiac neurodevelopment, and together with pediatric neurologists at Boston Children’s Hospital, Dr. Ortinau began another fetal MRI study. Preliminary results from both her CDI pilot study and the Boston project have shown that difference in brain development begin early in pregnancy for babies with heart defects. These include differences in brain size and how the outer part of the brain folds.

After gaining valuable experience working with experts in cardia neurodevelopment and fetal imaging, Dr. Ortinau returned to St. Louis, where the work she began in 2013 has continued with funding from a new CDI study launched last July. “The initial pilot study was key to designing the project in Boston. Then, what I learned from my work there was used as a platform to build on my new research here. It has come full circle,” Dr. Ortinau says.

“We were thrilled to welcome Cynthia back into our fold, says F. Sessions Cole, MD, chief of newborn medicine at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. “Her passion for ensuring our newborns have a fighting chance for healthy, happy, productive lives coupled with her intellectual curiosity will help improve the way we care for these babies and the understanding of the science behind it.”

One of the differences in the two studies is that Dr. Ortinau is now trying to focus more on why brain development tis different in babies with heart defects. She believes two potential mechanisms are important. The first that the heart defect likely affects how blood flow and oxygen are delivered to the brain. The second is that different genetic make-ups my lead to abnormal development of both the heart and the brain. In the first study, Dr. Ortinau’s team recruited only patients with isolated heart defects, meaning they had no other diagnosis. The second study will involve collecting data on all patients with heart defects, even those with other types of birth defects and will include genetic testing.

“A broader cohort, with the incorporation of genetic testing, will help us begin to understand the role different genetic variants play in both heart and brain development,” Dr. Ortinau says. “We will be able to see what the brains of different patients with different genetic variants look like in the hopes that we will being to find patterns. At the same time, measurements taken on blood flow and oxygen to the brain will help us narrow in on the physiological differences in the brains of these children.”

Dr. Ortinau hopes all this testing will lead to a day when expectant parents can leave their prenatal counseling session with peace of mind, knowing that no matter what must be done to repair their baby’s heart defect, their ability to learn, communicate, play and live their best life will be protected.