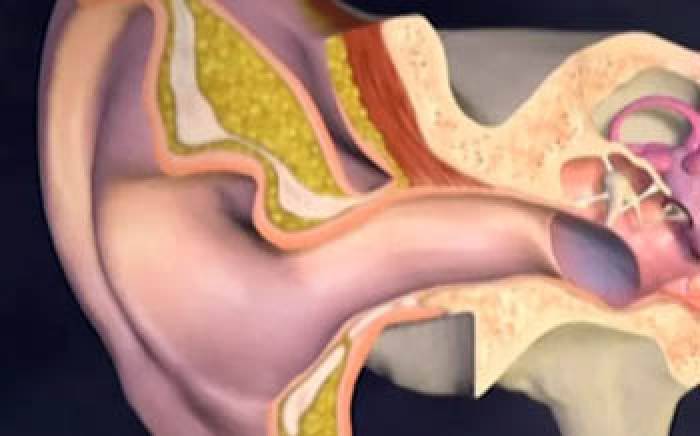

During normal hearing, sound waves travel through the ear canal and strike the eardrum causing it to vibrate. The eardrum is attached to three tiny bones in the middle ear. The last bone, the stapes, pushes on a fluid-filled chamber in the inner ear, called the cochlea. This fluid movement causes sensitive hair cells within the cochlea to bend. When the hair cells bend, they generate an electrical signal that is sent to the brain. Disease, damage, or deformity of the cochlear hair cells is a common cause of hearing impairment or deafness. These malfunctioning hair cells may send intermittent or unclear signals to the auditory nerve, or send no signal at all. A device called a cochlear implant can restore hearing by replacing these damaged structures with a wire that is implanted in the cochlea. In order to stimulate the hearing process, sound waves are first received by a microphone unit, or speech processor, that hangs over the back of the ear. Within the processor, sound is filtered and converted to a digital signal that travels to an antenna located on the head. From there, the signal is sent in the form of radio-like waves across the skin to an internal receiver embedded just under the scalp. This receiving unit then stimulates the wire implanted in the cochlea, enabling the cochlea to send clear signals to the auditory nerve. Although the surgery permanently damages the cochlea, cochlear implants can greatly improve hearing, even in people who are profoundly deaf. There are several potential complications associated with this procedure that should be discussed with the doctor prior to surgery.