What is antenatal hydronephrosis?

Antenatal (before birth) hydronephrosis (fluid-filled enlargement of the kidney) can be detected in a fetus by ultrasound as early as the first trimester of a pregnancy. During pregnancy, this condition is identified in 1 percent of males and 0.5 percent of females. Typically, this condition is not associated with abnormalities in other organ systems.

Antenatal (before birth) hydronephrosis (fluid-filled enlargement of the kidney) can be detected in a fetus by ultrasound as early as the first trimester of a pregnancy. During pregnancy, this condition is identified in 1 percent of males and 0.5 percent of females. Typically, this condition is not associated with abnormalities in other organ systems.

Prenatal intervention is almost never required, and amniotic fluid is usually normal. Depending upon the abnormality, ultrasound imaging may be needed throughout pregnancy and after a baby is born. In most cases, this diagnosis does not affect when, where or how a baby is delivered. Surgery is required in a small percentage of children during infancy and childhood.

What causes antenatal hydronephrosis?

1. Physiologic or benign dilation

This is the most commonly detected condition on prenatal imaging. This prenatal ultrasound image shows minimal renal pelvic dilation of less than 5 mm in both kidneys.

2. Ureteral obstruction or blockage

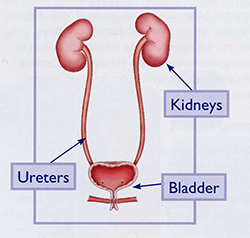

This may occur at one of two locations in the urinary tract:

- The most common site is where the renal pelvis joins the ureter (the duct by which urine passes from the kidney to the bladder). Ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJ) is estimated to be present in one in 1,000 infants.

- Obstruction may also occur where the ureter joins the bladder, known as ureterovesical junction obstruction (UVJ) or megaureter. The incidence of this condition is one in 2,500 infants and more than 90 percent of these cases improve without surgery.

3. Urethral obstruction (posterior urethral valves)

The most significant and concerning site of obstruction detected during pregnancy is found in the male urethra. A posterior valve affects the ability of the bladder to empty and as consequence, leads to dilation (expansion) of the kidneys.

4. Renal duplications anomalies

In most cases, a single ureter drains the kidney of urine. However, about 1 percent of all humans have two collecting tubes from a kidney. Most patients with this duplication have no identifiable abnormality. Obstruction of the upper tube (upper pole of the kidney) may occur in up to 1 in 5,000 children. Prenatal images often show dilation of only the upper part of the kidney. The ureter is also dilated because the obstruction occurs downstream at the level of the bladder. The distal ureter ends in an ureterocele (a balloon-like obstruction at the end of the ureter) or may be obstructed because it does not go into a normal location in the bladder.

5. Multicystic kidney

This is the result of complete obstruction of the ureter. As result, the kidney cannot produce urine and does not develop normally. The kidney has no function. Fortunately, this usually only affects one kidney. Given that the other kidney is normal (and compensates for the absence of another functioning kidney), infants with a multicystic kidney are usually born with entirely normal overall kidney function.

6. Vesicoureteral reflux

Vesicoureteral reflux occurs when the connection between the ureter and the bladder permits backflow of urine to the kidney. The normal flap valve mechanism does not function properly. The back-up of urine can cause waxing and waning dilation of the kidneys during pregnancy. Children with reflux are at higher risk for urinary tract infection and may be placed on preventive (prophylactic) antibiotics at birth.

Testing and treatment during pregnancy

In nearly all instances of antenatal hydronephrosis, ultrasound monitoring is all that is necessary. For most cases, a pregnancy is not affected, and a normal delivery can be performed. In the rare fetus with severe obstruction of both kidneys and insufficient amniotic fluid, prenatal intervention to relieve the obstruction is a consideration. Evaluation for possible intervention requires multiple specialties such as neonatology, pediatric urology and maternal-fetal medicine.

Testing and treatment following birth

Your baby may be placed on a low-dose, once-a-day antibiotic to prevent urinary tract infection.

Since an ultrasound performed in the first few days after your baby is born may underestimate the degree of this condition, the first ultrasound is usually conducted following discharge from the hospital.

However, there are circumstances when an ultrasound will be conducted prior to your baby’s discharge. This may be necessary because of:

- bilateral dilation

- decreased amniotic fluid

- complications following birth

- uncertainty regarding the ultrasound diagnosis

A voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG), which requires a catheter placed in the bladder, may be performed to diagnose vesicoureteral reflux, an abnormal flow of urine from the bladder to the upper urinary tract. This condition occurs in 5 to 25 percent of children with antenatal hydronephrosis. A diuretic renal scan, which requires an IV and a catheter, may be conducted in more severe cases to diagnose obstruction. The renal scan is more accurate if delayed until the baby is one month of age.

Children with vesicoureteral reflux may be treated with antibiotics to prevent urinary tract infection. They are monitored with periodic ultrasound and voiding cystograms. Children with an obstruction or blockage of the urinary tract may require surgical correction. In some babies, the evidence for obstruction is marginal or the degree of blockage is mild. In these babies, tests may be repeated after a few months. After all testing is complete, some babies have hydronephrosis without reflux or obstruction. These babies are usually followed with periodic ultrasounds to monitor the hydronephrosis and the growth of the kidneys.

For a baby with a multicystic kidney, the opposite kidney is usually normal. Unless the multicystic kidney is causing a problem with breathing or eating or there is a question of tumor or blockage, the kidney is usually left alone in infancy. Ultrasounds are usually performed at six months and one year of age. If the multicystic kidney is still large, removal is usually recommended.

For more information or to schedule an appointment, call St. Louis Children's Hospital at 314.454.5437 or 800.678.5437 or email us.