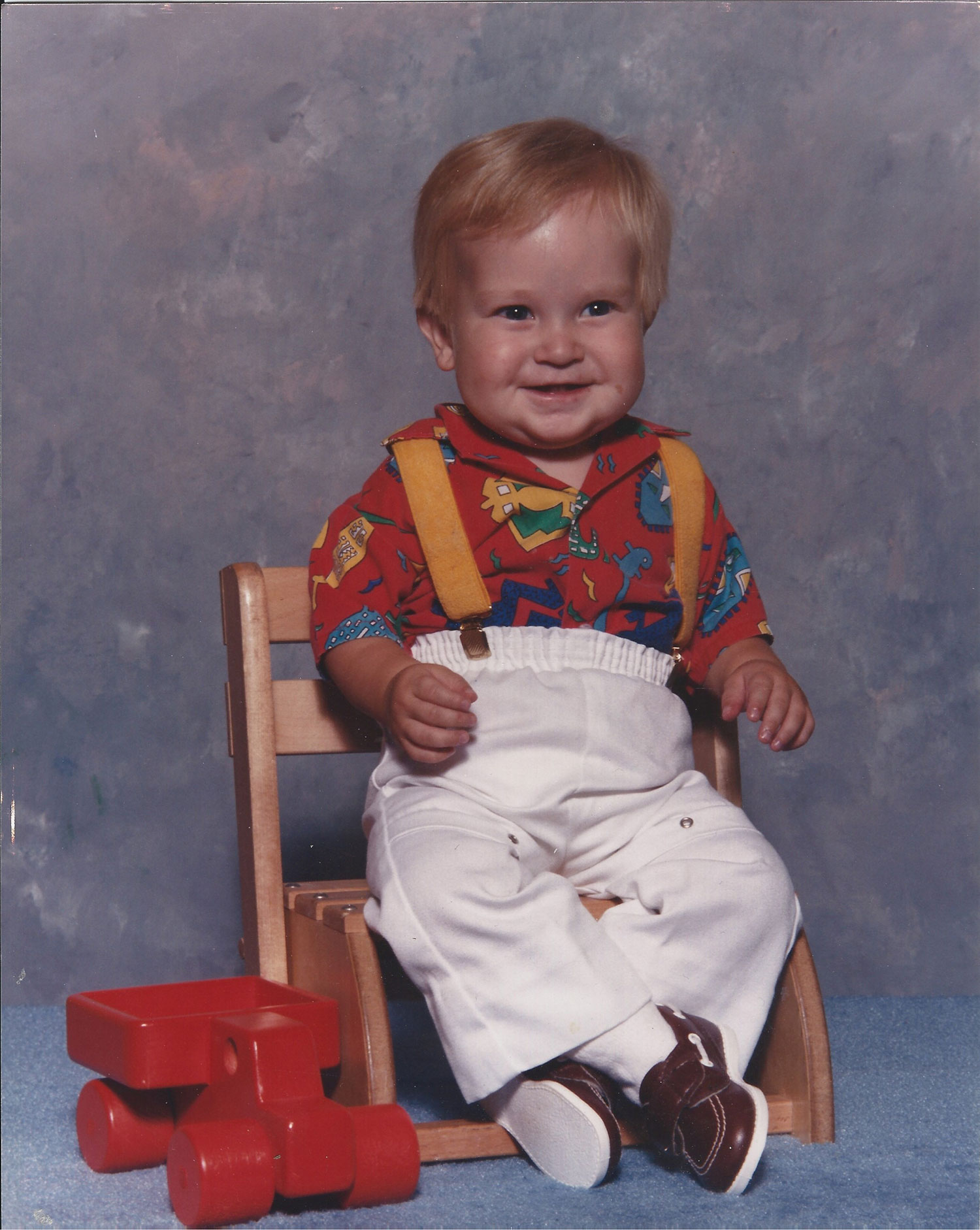

In 1987, at 18 months old, Alex Dixon was the first infant at St. Louis Children’s Hospital (SLCH) to successfully be treated with cardiac ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, a therapy that adds oxygen to blood and pumps it through the body. Earlier this year he had a valve replacement done at SLCH.

In 1987, at 18 months old, Alex Dixon was the first infant at St. Louis Children’s Hospital (SLCH) to successfully be treated with cardiac ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, a therapy that adds oxygen to blood and pumps it through the body. Earlier this year he had a valve replacement done at SLCH.

He is now 34 years old and thriving.

“I was a blue baby when I was born,” Dixon says. “I had bluish looking skin color because I was born with a congenital heart defect called Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), which is a primary cause of blue baby syndrome. I also had a leaky valve that would have to be repaired as I got older,” Dixon says.

TOF is a combination of four heart defects that can reduce blood flow to the lungs and allow oxygen-poor blood to flow out into the body. TOF happens when a baby’s heart does not form correctly as the baby grows and develops in the mother’s womb during pregnancy.

TOF is made up of the following four defects of the heart and its blood vessels:

- There is a hole in the wall between the two lower chambers ― or ventricles ― of the heart.

- There is a narrowing of the pulmonary valve and main pulmonary artery.

- The aortic valve, which opens to the aorta, is enlarged and seems to open from both ventricles, rather than from the left ventricle only, as in a normal heart.

- The muscular wall of the lower right chamber of the heart (right ventricle) is thicker than normal.

When Dixon was 9 months old, his surgeons performed a BT shunt procedure that connected the subclavian artery to the pulmonary artery, which helped increase blood flow to Dixon’s lungs. At 18 months, Dixon had open-heart surgery to correct his heart defects and was then placed on ECMO.

“With ECMO, blood is pumped outside of the body to a heart-lung machine that removes carbon dioxide and sends oxygen-filled blood back to tissues in the body,” says Charles Canter, MD, St. Louis Children’s Hospital pediatric cardiologist. “Blood flows from the right side of the heart to the membrane oxygenator in the heart-lung machine, and then is rewarmed and sent back to the body. This method allows the blood to ‘bypass’ the heart and lungs, allowing these organs to rest and heal.”

“I didn’t have any more surgeries until the year 2000, when I felt fatigued and went to a hospital in Kansas City to have a left pulmonary stent put in,” Dixon says. “Then in 2007, I had a human donor valve put in at SLCH and I felt really great after that.”

Dixon continued to have regular check-ups, went off to college, transitioned to a cardiac physician for adults and saw a cardiologist in Texas while he lived there. He moved back to St. Louis last year and had a check up this past January. “I had an ECHO done and it was discovered that it was time for a new valve because the current valve was leaking,” Dixon says.

He received what is called a Melody valve in a procedure that took place at SLCH.

He received what is called a Melody valve in a procedure that took place at SLCH.

“TOF often leaves the patient with a leaky pulmonary valve,” says David Balzer, MD, St. Louis Children’s Hospital cardiologist. “Blood leaks backwards in the heart and results in progressive enlargement of the heart. That can be repaired with a Melody valve.”

The Melody valve, a jugular vein from a cow, is a replacement pulmonary heart valve, Dr. Balzer says. “It's used to replace a blocked or leaky valve that has been previously repaired to correct congenital heart defects present at birth. The Melody valve is not a replacement for open-heart surgery, but it helps decrease the number of surgeries a patient may have over time. By successfully repairing the valve, Alex was able to delay or avoid another open-heart surgery,” says Dr. Balzer.

The Melody valve was approved by the FDA in February 2010, and St. Louis Children’s Hospital was one of the first hospitals to implant the valve. “It’s exciting for the patients and their families,” says Dr. Balzer. “They do not look forward to a lifetime of repeated operations, and for us, it’s very exciting to be able to participate in that.”

Dr. Balzer and his team have performed more than 400 Melody valve replacements.

“We are able to care for patients from infancy well into adulthood through our commitment and focus on a continuum of care and with our relationship with Barnes-Jewish Hospital and the Center for Adults with Congenital Heart Disease (ACHD) at the Washington University and Barnes-Jewish Heart & Vascular Center,” adds Dr. Canter. “As these children grow up they continue to face medical issues and we work closely with physicians at Barnes Jewish Hospital and Washington University to treat patients from birth throughout their lives and Alex is a true example of that.”

“The Melody valve replacement was a success — and I have no limitations and am living a healthy life,” Dixon says. “The care I have experienced at St. Louis Children’s Hospital has been nothing but outstanding. Doctors and staff at SLCH are the best and they provide wonderful, expert care I can trust with my life.”

For more information about Center for Adults with Congenital Heart Disease (ACHD) at the Washington University and Barnes-Jewish Heart & Vascular Center click here.