In 2010, just two days before Christmas, Colleen and Mike Miller learned that their 6-month-old daughter, Layla, suffered from dilated cardiomyopathy. As a registered nurse with cardiac care experience, Colleen Miller knew her family’s life would never be the same from that day forward.

“When the diagnosis was cardiomyopathy, we felt like we were given a death sentence,” she says. “More than half of all children diagnosed don’t live past age 5. If they do survive, it is a fluke or due to a heart transplant, and that is not a cure, since the life span of a new heart is only around 10 to 15 years.”

Layla spent her first Christmas in the cardiac intensive care unit at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, and had many more hospitalizations, tests, medical and surgical procedures after that. The Millers’ lives became filled with doctors’ appointments, medication schedules and worry, knowing the whole time that a transplant loomed in their future. That time came in August 2014.

Unfortunately, Layla passed away after going into cardiac arrest during a cardiac catheterization meant to determine the readiness of her lungs to handle a new heart.

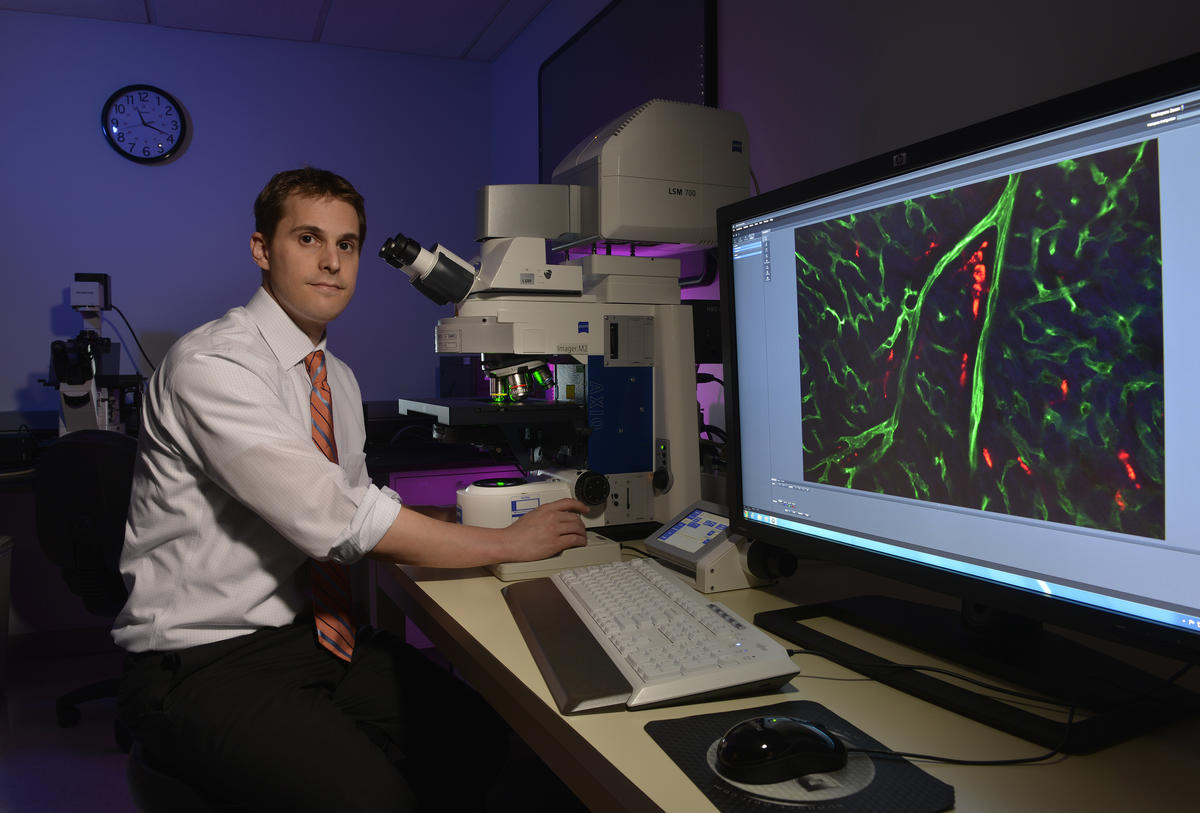

A recent discovery by Washington University cardiologist Kory Lavine, MD, PhD, and his collaborators, may be a step toward better understanding cardiomyopathy in children and eventually developing effective therapies. Their research, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, identified the underlying reason why children with heart failure do not respond to therapies typically used in adult patients.

Heart failure medications currently used in adults target a process called adverse remodeling, a common mechanism by which the adult heart responds to injury. Typical drugs such as beta blockers and ACE inhibitors function to halt or slow down the remodeling process, reducing scar deposition and maladaptive remodeling of cardiac tissue. Dr. Lavine’s lab proved that adverse remodeling does not happen in children with heart failure. These findings provide a framework to understand why current treatments for heart failure do not work for children and signal that new approaches are needed.

Through a grant funded by the Children’s Discovery Institute, a research partnership between St. Louis Children’s Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Dr. Lavine’s lab is beginning to develop new strategies for pediatric heart failure. The researchers are inserting genetic mutations identified in children with heart failure into translucent zebrafish. They then employ advanced imaging techniques to understand why each pediatric heart failure mutation results in cardiac dysfunction and screen for drugs that may serve as precision therapies to treat an individual child’s mutation.

“We hope to get to the day when a patient gets diagnosed with heart failure and undergoes routine genetic screening. For children who carry a heart failure mutation, we hope to either have identified drugs that target their mutation or engineer a zebrafish line to better understand their disease and identify drugs with the potential to reverse the course of their illness,” Dr. Lavine says.

“We were happy to assist Dr. Lavine in this study. His findings are intriguing as there are concerns that pediatric heart failure may not respond as well to medications used to treat adult heart failure,” says Washington University pediatric cardiologist Charles Canter, MD, medical director of the cardiac transplant program at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. “Dr. Kathleen Simpson and I plan to extend this work through the National Institutes of Health-funded Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry via an additional grant she recently received from the Children’s Cardiomyopathy Foundation.”

Since losing Layla, the Millers have worked to raise awareness of a condition that has no cure, limited treatment, high mortality and needs more funding to find a cure. They also have channeled their grief into acts of kindness, such as purchasing a rocking chair for the cardiac ICU where they spent so much time. The chair has a plaque with Layla’s name and a quote that has sustained the Millers through it all. It reads: “There is no foot too small that it can’t leave an imprint on this world.”